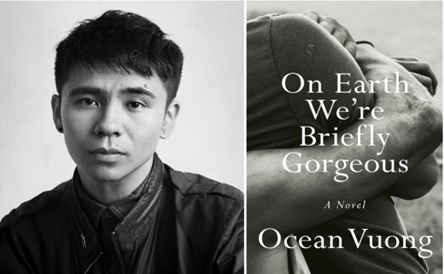

Ocean Vuong: Speaking the Unspeakable

A book review of Ocean Vuong’s “On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous”

by Angeline Marie C. Yambao

Suppose you are looking for something to ground you into being a Filipino or getting in touch with your rich heritage and fully encapsulate Taylor Swift’s “All Too Well,” a 10-minute version of recently released music. This serves to have a justifiable moment for you to enter the gunshot wounds of the past and transcend beyond the ordinary heartache while you read. In that case, the award-winning Vietnamese American poet slash novelist Ocean Vuong’s debut novel, “On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous,” is the book for you to grab and never let go.

Ocean Vuong’s literary composition, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, had enraptured the world with its unraveling truth and had bypassed against the limits of a borrowed language coming from an immigrant whose preservation of life was due to the countenance of being thrust upon war. The epistolary novel was published by the Penguin Press on the 4th of June 2019. Make no mistake, Ocean Vuong is also the author of both the rhythmic literary work, the Night Sky with Exit Wounds (2016) and Time is a Mother (2019). The number of credentials under his name governed through his literary masterpiece is attested by being New York Times’ Bestseller, winner of the T.S. Elliot Prize, the Kundiman Fellowship, MacArthur Fellow, Dylan Thomas Prize, the NAAAP Pride Award, and the rest.

Little Dog & Ocean Vuong-“Immortalizing the Human Language.”

The novel unravels itself into the plot of a letter, poetically written by a son whose mother cannot read from the depths of the ink of what has been conveyed through the once blank slate of parched paper. The opening line begins: “Dear Ma, I am writing to reach you, even if the word I put down is one word further from where you are” And although the inevitable truth has been thrust upon him, he continues to write in a desperate attempt to hold a semblance of normality that illiteracy does not play a border of isolation between mother and son.

But something so raw and hidden cannot be easily touched by a gentle, forgiving hand. Because to be handled so lovingly is to break apart in light-years, in small atomic rays that are foreign. Because to be acknowledged is to have reigned in defeat that you have fought and survived parallels of war.

The absence of a gold medal is merely left on the tirade in the Vietnam War for soldiers. While his mother, Rose, is left to a foreign land and with a local tongue that is of no use. For the reason that her education was seized at the tender age of five, after a napalm raid had destroyed her schoolhouse in Vietnam – the school wasn’t the only thing left burning in those wildfires. It had left generations of predecessors to be burnt into existence and be extinguished in a blink of an eye, that no amount of anesthesia, surgery, and bandages can heal the burnt wound.

Vulnerably penned by the hands of a child, by her beloved son, Little Dog, who in his late twenties excavated an heirloom of concealed truths which demands him to conform to the reality that began before he had even existed. A historical fragment whose core can be traced to the fragile roots of the Vietnam war.

Thus, the question remains amongst his texts: “When does a war end? When can I say your name, and have it mean only your name and not what you left behind?” Because just as he has been called as Little Dog by his grandmother, Lan for a reason: “to love something is to name it after something so worthless it might be left untouched and alive.” And he is the acute and terrible air that hangs with a wound of grief that causes him to bleed, maybe sweat, or perhaps it was tears that causes him to never cease to write and boldly conquer the universal language itself that was once a scab.

Freedom Is Not a Small Price

Ocean Vuong assumes the voice of Little Dog in each stanza, words, and grappling depictions of the life being lived within those fruitful times. He writes as a witness to the panic-stricken horrors reflected through the eyes of survivors just as those names are etched and stitched within the lines: Lan, who was his grandmother that had run away from an arranged marriage, decidedly lived a life as a prostitute to survive the Vietnam War but she had found herself a type of love before schizophrenia took over, but an illness was never enough to make Lan weak in front of her grandson, she shielded him as much as she’d nurtured him through stories of hope.

Because Lan, no matter how scarce the food is, never forgets to offer and feed the young; “They say good soldiers only win when their grandmas feed them.”

This is why Rose continued to blossom and never retreated away from a battle because the apple never fell far from the tree it bore. Rose, Lan’s daughter, and Mai’s sister were byproducts of belonging to a biracial race. Having a Vietnamese mother and an American John of a father, who’s to say they fit within Vietnam?

They were perceived to be supporting the enemy in their homeland. Because as Ocean recalls his mother’s past, Rose became the “ghost-girl” of Vietnam where the children threw excrements to make her skin browner, scraping the paleness off of her skin with a spoon in the hopes of making it in the likeness representation of goodness that colors their skin.

Because cutting one’s auburn light hair was not enough, it was never enough for everyone nor anyone that wanted a taste of power and was coerced by fear. It’d make you humorlessly laugh that war brought by a nation was more damaging than it ever would be reversed through time. It’d implant a seed of doubt that as if to be born-half white is a sin, a wrong to be changed, but Rose, similar to her name, still had the power to utter aloud the word: “Đẹp Quá,” which translates to being very beautiful in Vietnamese and just like her son, it was far more than enough.

They’d come to say that time heals all wounds, and for Mai, it held a guise of truth. Mai, Rose’s little sister, was far too accustomed to the red that splatters her lip from an impact of a fist, a bruising blue at the tip of her arms, a sickening yellow that mixes with the ointment as if it was declining to be treated ever so kindly, and the overly familiar purple that stains her left eye. But as they say, time heals all wounds, and she eventually steps out of reach from the inflictor of the scab that refuses to put a rest to the abuse.

A woman who survived: being Vietnamese in a foreign land, a sister to Rose, a daughter to Lan, and an aunt to Little Dog to whom she was held where aches did not come. Thus, it’d take more than a man to keep her locked up in a cell of fear.

In Greek Mythology, termed by Plato, you’d commonly hear that “humans were originally created with four arms, four legs, and a round head with two faces. Fearing their power, Zeus split them into two separate parts condemning them to spend their lives in search of their other halves.” This passage was what perfectly illustrates Paul, Little Dog’s grandfather, because not all forms of love are equally accepted within the time of service to your nation-because to have fallen for a Vietnamese as an American soldier, to have promised and bred a future was merely placed in brief moments of permanence to Lan.

But the one thing that remains true and in the line of defense was how Paul proclaimed that Little Dog was as much to himself as to the rest of them because he had loved Little Dog’s other counterparts even before he was born through Rose: “This is my grandson. My grandson.” Somehow, he had belonged somewhere within the American soil which

For the lack of a better word of an insult, Marin was called a “faggot” for being a transgender woman within the Connecticut neighborhood when Little Dog was nothing but a young boy. He’d never come to know why he stops and pauses to look at Marin, but the courageous way how she never knelt in submission nor lowered her head in shame was enough for Little Dog to give respect. A woman such as Marin, she’d continue to wear her high heel shoes and dismiss the “men” who’d threaten her comfort for not conforming to traditional ideas that everyone was used to. Queer communities are often visited by the brute force of violence and discrimination within American land.

Then comes next is Trevor, the boyishly handsome grandson of where Little Dog is working in the tobacco farm, where low wages, overworking hours, and immigrants come to reside. From a glance, Trevor was undeniably American from head to toe, and he’s been built as the next protegee through the grit of muscles and bone within the American Masculinity of belief.

Maybe this time, the hit Trevor’s been expecting wouldn’t be coming from his father nor from the bullets of assault of manhood. Instead, it went from a boy who’d say “Lo Siento,” sorry, to him when he first introduced his name. Because as much as he denied, Trevor was the one who’d said the tender words of comfort that throbbed: “Don’t be scared. You’re smart.” because boys like him were closeted away before he could utter a word to scream for help.

Lastly, Mrs. Callahan was a teacher in Hartford, Connecticut, but as just much as she teaches her students – it’s undeniable how her power was able to make Little Dog take the first step to speak and read as his shoulders shake from the gentle acts of kindness. The smooth strokes, the clear diction, the slow, tentative steps, and the warm gaze of Mrs. Callahan was enough for him to read his first verse: “I was enamored by this act, it’s a precarious yet bold refusal of common sense” to surrender to fear through education.

On that day, Little Dog decided to become the sole translator of the English language of his family, and he’d gripped the rough edges of the texts, he’d stutter, he’d butcher, he’d stumble, but he’d eventually come to master the language. A language that could not be spoken out loud, much less even read alone, has now been engraved into his bones, saying: Ma, I’ve made it.

Something For Anyone & Everyone

Ocean Vuong had made “On Earth, We’re Briefly Gorgeous” because it had aimed to piece together the identity of each humankind before they became who they are now – something never been said but was always questioned, who were you before you became the one, I come to know? He’d successfully delivered an eloquence of understanding on how both the physical and psychological trauma residing within the human body affects not only the beholder but as well as everyone within.

The novel aims to address the disturbing reality of how war and all forms of violence are being propositioned to others: of how race, class, toxic masculinity, psychological disorders, domestic abuse, education inequality, immigration, social class, minimum wage, cognitive dissonance, addiction, and the glorification in the American Dream of prosperity are the wars which continue to exist within the modern world. Nevertheless, Ocean had made it clear that as there it was, there are moments of unbinding bliss that last forever.

Guided by the touch of human kindness, compassion, and tenderness that makes the impossible come to be possible in this era. The remaining question in his book is, how do you survive the turmoils of war and welcome the luxury of love from what originated as something beyond the scope of recovery. “All this time, I told myself we were born from war—but I was wrong, Ma. We were born from beauty. Let no one mistake us for the fruit of violence—but that violence, having passed through the fruit, failed to spoil it.”

We invite you all to read through this art piece of a book by Ocean Vuong, On Earth, We’re Briefly Gorgeous – that captures the life being lived without an ounce of the filter or shame.